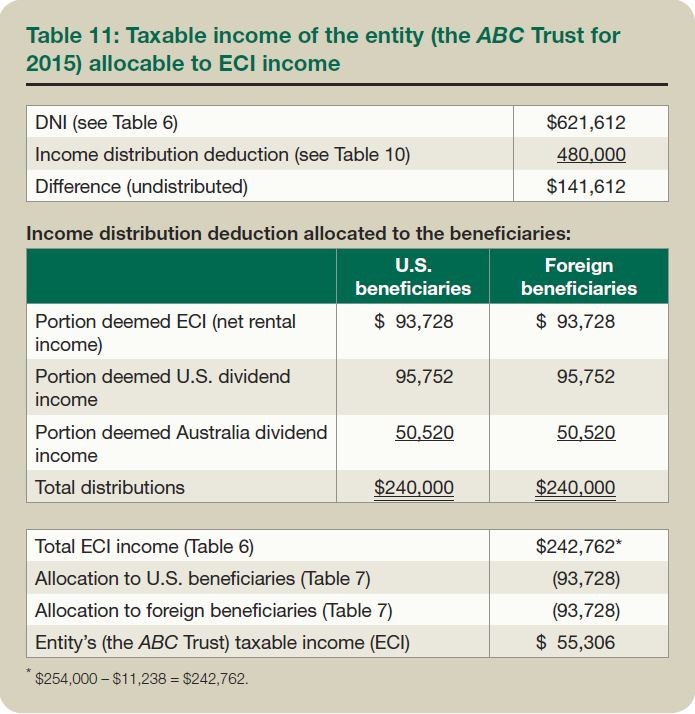

Above is the Foreign Grantor Trust Beneficiary Statement from the 3520-A

If it’s a FNGT? The U.S. beneficiary should receive a Foreign Non Grantor Trust Beneficiary Statement which includes information about the taxability of distributions they have received and foreign trust income they must report.

- The U.S. tax consequences and tax reporting requirements for a trust are determined by the residence and classification of the trust and its fiduciary.

- A trust is considered a foreign trust unless it meets the “court” and “control” tests. A trust may be an “ordinary” trust or a “business” trust, as described in the regulations. A business trust will not be treated as a trust for purposes of the trust rules in Subchapter J of the Code.

- A foreign nongrantor trust is treated for U.S. tax purposes as a nonresident alien individual who is not present in the United States at any time. The trust is taxed on income effectively connected with a U.S. trade or business at the graduated rates applying to domestic trusts and on income that is not effectively connected with a U.S. trade or business (fixed or determinable, annual or periodic income, or FDAP income) at a flat 30% rate.

- Foreign nongrantor trusts are generally subject under different Code sections to withholding on FDAP, U.S. real property interests, and effectively connected income they receive as partners in a U.S. partnership under Sec. 1446.

- The trustee of a nongrantor trust may be required to report U.S.-source income and tax withholding for the trust and the allocation of estimated income tax payments to the trust’s beneficiaries, as well as on a foreign nongrantor trust beneficiary statement.

- The U.S. beneficiary of a foreign trust is required to report distributions from the trust on Form 3520, Annual Return to Report Transactions With Foreign Trusts and Receipt of Certain Foreign Gifts. A U.S. beneficiary who holds foreign assets or has foreign accounts may also be required to file Form 8938, Statement of Specified Foreign Financial Assets, and FinCen Form 114, Report of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts (FBAR).

- A nonresident alien beneficiary of a foreign nongrantor trust may also have to file Form 1040NR, U.S. Nonresident Alien Income Tax Return, in certain situations.

The evolution of the world economy and the increasingly mobile society present challenges for successfully administering foreign trusts and estates for fiduciaries, beneficiaries, and practitioners. The trust concept has expanded into foreign jurisdictions, even civil law jurisdictions. Administering a foreign trust or estate with U.S. beneficiaries entails additional fiduciary responsibilities that call for the fiduciary to seek knowledgeable and experienced professionals to guide the fiduciary in his or her administrative duties and tax compliance requirements under current U.S. laws and regulations.

That standard of prudence is even more profound today because of tax information exchange agreements between foreign governments and the United States. The standards for transparency and exchange of tax information were developed by Treasury’s FATCA implementation, including Intergovernmental Agreements (IGAs), and by the Organisation for Economic Co–operation and Development (OECD) implementation of its Common Reporting Standard. The challenges of administering a foreign trust or estate are complex because each of the various tax jurisdictions has its own “source–income” rules and tax reporting requirements, which might affect the entity and its beneficiaries. The potential complexity and risks of penalties for noncompliance necessitate coordination and communication between practitioners and fiduciaries to carefully administer and monitor the execution of the payment of distributions and the resulting tax reporting before transactions are finalized.

Prudent foreign trust and estate administration should consider a number of crucial factors, including:

- Determing each beneficiary’s proper income tax filing status and supporting it with documentation, including signed tax information statements;

- Analyzing the relevance of pertinent tax treaty provisions, depending upon the source-income rules and tax jurisdictional laws;

- Proper allocation of receipts and disbursements between income and principal under local law and the trust’s or estate’s governing instruments;2

- Engaging knowledgeable and experienced professionals in each tax jurisdiction to ensure that tax compliance is maintained;

- Following an informed, careful, and planned course of action before procedures are implemented.

In addition, as discussed in a previous article by this author,3 the settlor’s decision in designating a fiduciary and successor is critical when the future estate will include foreign beneficiaries (and the same care is advised for foreign trusts and estates with U.S. beneficiaries). That article also contains additional comments regarding the exercise of prudent care and due diligence in the entity’s administration.

This three–part article will focus on the U.S. tax reporting and classification of “foreign nongrantor trusts” and “foreign estates,” with both U.S. and foreign beneficiaries. Thus, this article does not address a foreign grantor trust (i.e., Sec. 672(f)) or a U.S. grantor trust created by a U.S. person who transferred assets to a foreign trust (i.e., Sec. 679). This article mentions some specific tax reporting issues under U.S. tax laws, which are analyzed in the author’s previous articles.4 In some cases these issues are cross–referenced to the earlier articles. Determining the proper tax classification of the trust or estate entity for U.S. tax purposes is critical for the fiduciary and his or her advisers.

Evolution of the discretionary trust concept

Global jurisdictional tax laws and the corresponding tax reporting requirements change frequently, directly affecting the trust entity and its beneficiaries. These global trends have evolved into greater transparency and exchange of tax information ushered in by FATCA and the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard. The discretionary trust has adapted to these changes, which afford flexibility in terms of the tax obligations allocated to the trust’s global beneficiaries and the trust itself.

The value of sound professional advice to fiduciaries in their pursuit of successful trust administration has also increased. For example, fiduciaries are advised to exercise their discretionary powers to allocate a portion of the U.S. tax liability to the beneficiaries and elect to allocate an applicable share of the tax withholding to each beneficiary. The remaining tax liability is reported by the trust after the fiduciaries have analyzed the resulting tax burdens to both the entity and its beneficiaries to determine the optimum economic consequences.

How to determine whether a trust is a foreign trust

The U.S. tax consequences and tax reporting requirements for a trust or estate are determined by the residence and classification of the entity and its fiduciary. After 1996, the Small Business Job Protection Act of 19965 provides specific tax classification criteria to differentiate the foreign or domestic tax status of trusts with both foreign and domestic participants. Under Secs. 7701(a)(30)(E) and (31)(B),6 a trust is classified as a foreign trust unless both of the following conditions are satisfied:

- A U.S. court must be able to exercise primary supervision over administration of the trust; and

- One or more U.S. persons must have authority to control all substantial decisions of the trust.

To allow a trust a “reasonable period of time” to take corrective actions, in the event of an inadvertent change in fiduciaries,7 Treasury regulations allow a 12–month period for corrective action to maintain the entity’s domestic status.8 For example, if a U.S. trustee dies or abruptly resigns, and the trust now has a foreign fiduciary to replace the former U.S. trustee or the foreign fiduciary acts as a co–trustee with a new U.S. trustee, the trust would be classified as a foreign trust. Using these criteria, a trust can be classified as a “foreign trust,” even if it was created by a settlor who is a U.S. person, all of its assets are located in the United States, and all of its beneficiaries are U.S. persons. Thus, if one foreign person, such as a “trust protector,” has control over one “substantial” power to control decisions affecting the trust, that trust is classified as a foreign trust. Regardless of the Code provisions above, the two legal requirements fall short of establishing the “bright line test” that lawmakers intended. Treasury provided some clarity in Regs. Sec. 301.7701–7(d)(2). The regulations stipulate that a trust is a U.S. person (i.e., a domestic trust) on any day that the trust meets both the “court test” and the “control test.”

The court test

A trust satisfies the court test if the following three requirements are met:9

- The terms of the trust instrument do not direct that the trust be administered outside of the United States;

- The trust is in fact administered exclusively in the United States (i.e., a U.S. court has “primary supervision”); and

- The trust is not subject to an automatic migration provision as described in Regs. Sec. 301.7701-7(c)(4)(ii), which means the trust instrument contains a provision under which the trust will automatically be relocated to another country if a U.S. court attempts to assert jurisdiction over the trust.

For these purposes, “court” includes federal as well as state and local courts within the 50 states and the District of Columbia.10 “Primary supervision” under the regulations means the judicial “authority to determine substantially all issues regarding the administration of the entire trust . . . notwithstanding the fact that another court has jurisdiction over a trustee, a beneficiary, or trust property.” The regulations provide a nonexclusive list of four types of trusts that satisfy the court test:11

- Trusts that are registered in a U.S. court by an authorized fiduciary under a state statute similar to the Uniform Probate Code, Article VII, “Trust Administration”;12

- Testamentary trusts, if all the fiduciaries have been qualified as trustees by a U.S. court;

- Inter vivos trusts, if the fiduciaries and/or beneficiaries take action in the event of the settlor’s death in a U.S. court to cause the administration of the trust to be subject to the court’s primary supervision; and

- Trusts that are subject to primary supervision for administration by a U.S. court and a foreign court.

The control test

Regs. Sec. 301.7701–7(d)(1) provides the following criteria to satisfy the control test:

- A “U.S. person” means a person qualifying within the meaning of Sec. 7701(a)(30).

- “Substantial decisions” mean all decisions other than ministerial decisions that any person, whether or not acting in a fiduciary capacity, is authorized or required to make, either under applicable law or the trust instrument. Those decisions include the primary powers assigned to a fiduciary such as making distributions, designating beneficiaries, allocating income and principal for trust transactions, terminating the trust, handling disposition of trust claims, removing or adding a trustee or co-trustee, appointing a successor trustee, and making trust investment decisions.13

- “Control” means that no other person has the power to veto any of the fiduciary’s substantial decisions.14

As previously discussed, the IRS regulations give the trust 12 months to correct an inadvertent change in trustee that causes an unintended loss of U.S. tax status, such as a trustee’s resignation, disability, or death (but not removal) or the trustee ceasing to be a U.S. person (i.e., change of residency or expatriation). Thus, the trust is able to make whatever changes are necessary to give control over all substantial decisions of the trust to a U.S. person.15 A change of trustee due to removal or appointment is not inadvertent under the regulations. If corrective actions are successfully undertaken within the 12–month period, the trust will be treated as having maintained its U.S. tax status for the entire period. This result would occur even if one or more substantial decisions were not controlled by a U.S. person during the 12–month period.

Caution: If a change in the trust’s fiduciary causes a change in the trust’s residence from a U.S. domestic trust to a foreign trust (if no corrective actions were successful by the end of the 12–month period), that change is treated for U.S. tax purposes as a transfer to a foreign trust.16 That transfer is subject to immediate tax (gain recognition) under Sec. 684. Thus, trust income tax returns would be required to be filed reporting the trust transactions before the change of residency (as a domestic trust) and for the remaining period of the tax year (as a foreign trust). The IRS district director having jurisdiction over the trust’s tax return filing has authority to grant the trust an extension of time to make the necessary corrective actions, if a written statement is sent setting forth the reasons for failure to meet the time requirements, under reasonable–cause standards.17

Trust entity classifications based upon IRS regulations

A trust’s “tax status” classification is critical from the standpoint of both fulfilling its purpose and operations, as well as the proper tax treatment and reporting under the Code and regulations. Correctly confirming the tax status classification is imperative in properly reporting a foreign nongrantor trust’s transactions for U.S. tax purposes. In analyzing the classification, determining whether the trust qualifies under the regulations as an “ordinary trust” or as a “business trust” will dictate the proper tax treatment for the entity’s transactions. An entity qualifying as a “business trust” may not be treated as a trust under Subchapter J of the Code.18

Ordinary trusts: Regs. Sec. 301.7701-4(a)

In general, the term “trust” as used in the Code refers to an arrangement created either by a will or by an inter vivos declaration, whereby a trustee takes title to property to protect or conserve it for the beneficiaries’ benefit under the ordinary rules applied in chancery or probate courts. The beneficiaries cannot share in the discharge of this responsibility, and therefore, are not associates in a joint enterprise for the conduct of business for profit.19

Business trusts: Regs. Sec. 301.7701-4(b)

Business trusts (or commercial trusts) generally are created by the beneficiaries simply as a device to carry on a profit–making business that normally would have been carried out through business organizations that are classified as corporations or partnerships under the Code.20 That type of organization is more properly classified as a business entity. The legal form of the organization will not, in itself, cause an organization to be treated as a trust for federal income tax purposes.

The fact that an organization is technically created in a trust formation by conveying title of property to trustees for the benefit of persons designated as beneficiaries will not convert the entity into a trust if the organization is more properly classified as a business entity under Regs. Sec. 301.7701–2. For example, the absence of formal corporate attributes (e.g., officers, bylaws, certificates, or a seal) may provide little proof as to the taxpayer’s true character.21 Although the regulations refer to a business trust as being either a corporation or a partnership, a business trust may also be a disregarded entity.22

Investment trusts: Regs. Sec. 301.7701-4(c)(1)

An investment trust will not be classified as a trust if the trust agreement permits varying of the certificate holders’ investment.23 An investment trust with a single class of ownership interests, representing undivided beneficial interests in the trust’s assets, will be classified as a trust if there is no power under the trust agreement to vary the investment of the certificate holders.

Because of the complexity of laws in foreign jurisdictions where the trust might have been created, it can be more difficult to properly classify the trust entity and its operations. An investment trust with multiple classes of ownership interests ordinarily will be classified as a business trust.24 If the trust is properly classified as a business entity under Regs. Sec. 301.7701–2, it can choose under the check–the–box election whether to be taxed as a corporation or a partnership for federal income tax purposes. However, caution is needed as the check–the–box regulations are different for foreign entitiesthan for domestic entities. The settlor’s intent, as expressed in the trust instrument, and the operations of the entity will most likely determine the applicable tax status classification under the guidelines analyzed above.

U.S. tax treatment of foreign nongrantor trusts

A nongrantor trust is treated as its own taxpayer, separate from the grantor or settlor. Generally, a foreign nongrantor trust determines its taxable income the same way an individual does. However, Secs. 642, 643, 651, and 661 provide for certain modifications. For U.S. tax purposes, a foreign nongrantor trust is treated as a nonresident alien (NRA) individual who is not present in the United States at any time.25 A 30% tax is imposed on the net capital gains of an NRA who is present in the United States for 183 or more days during a tax year if those gains are allocable to sources within the United States. As a result of the Sec. 641(b) amendment, a foreign nongrantor trust is not taxed on U.S.-source capital gains (except for gains resulting from the sale of a U.S. real property interest, which is treated as effectively connected income (ECI) with a U.S. trade or business under Sec. 897(a)). Thus, even if the trustee(s) of a foreign nongrantor trust permanently resides in the United States (but the trust entity continues to qualify as a foreign trust, as previously discussed in this article), the trust will be treated for U.S. tax purposes as if the trustee(s) had never been present in the United States during the tax year.

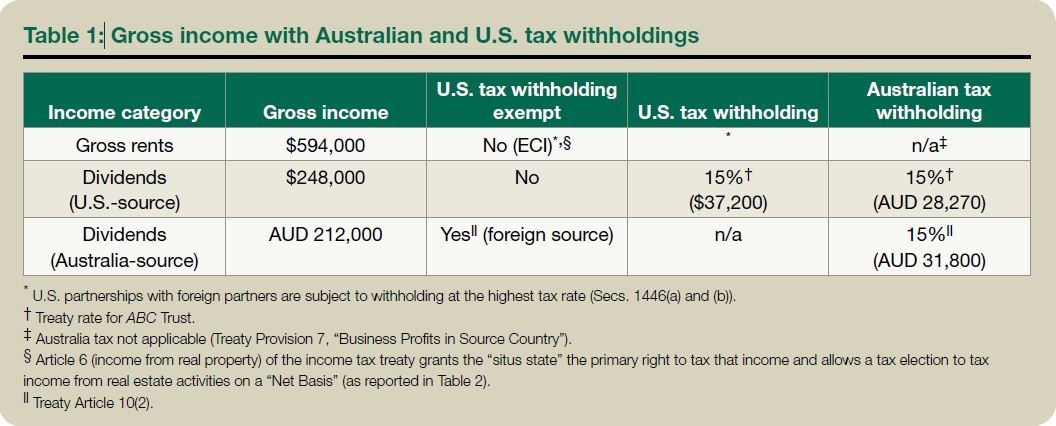

Gross income of a foreign nongrantor trust for U.S. tax purposes

The gross income of a foreign nongrantor trust consists of:

- Gross income derived from U.S. sources that is not effectively connected with the conduct of a U.S. trade or business within the United States;26

- Gross income that is effectively connected with the conduct of a trade or business within the United States;27 and

- Foreign-source income.28

Gross income from sources within the United States includes:

- Interest income from the United States (or any of its agencies), the District of Columbia, noncorporate residents of the United States, and domestic corporations;29

- Dividend income from domestic corporations;30

- Rental and royalty income from property located in the United States, including income from the use in the United States of patents, copyrights, secret processes and formulas, goodwill, trademarks, trade brands, franchises, and the like;31

- Gains from the disposition of U.S. real property (as defined in Sec. 897(c));32 and

- Income that is effectively connected with the conduct of a trade or business in the United States (i.e., ECI).33

Note: While foreign nongrantor trusts do not normally engage in a U.S. trade or business, they may invest in partnerships that engage in a U.S. trade or business, resulting in the trusts’ having ECI.34 For a foreign nongrantor trust to be subject to U.S. tax on ECI, the foreign–person entity must have a “permanent establishment” in the United States to operate or conduct that business. Permanent establishment is defined under U.S. international principles and/or an applicable income tax treaty provision. When a foreign nongrantor trust is a general or limited partner in a U.S. partnership that is engaged in a U.S. trade or business, the trust is deemed to be engaged in that trade or business.35

Dispositions of U.S. real property interests

When a foreign nongrantor trust disposes of a U.S. real property interest (USRPI), the gain is treated as ECI.36 A USRPI is an interest in either:

- Real property located in the United States or the U.S. Virgin Islands; or

- A domestic corporation, unless it is established that the corporation was not a USRPI property-holding corporation within the period described in Sec. 897(c)(1)(A)(ii).37

For these purposes, “interests in real property” include fee ownership, co–ownership, and leaseholds of land, improvements thereon, any associated personal property, and options to acquire any of those interests.38 If a foreign nongrantor trust receives consideration for disposing of an interest in a partnership that holds USRPIs, that consideration will be treated as consideration for the disposition of a USRPI.39 The Foreign Investment in Real Property Tax Act of 1980 (FIRPTA) imposes a tax on the disposition of those USRPIs. A USRPI includes a U.S. real property holding company (USRPHC), which, under Sec. 897(c)(2), is defined as any corporation in which the fair market value (FMV) of its USRPI equals or exceeds 50% of the sum of the FMV of its (1) USRPIs; (2) interests in real property located outside of the United States; and (3) other assets used or held for use in a trade or business. Sec. 1445 provides that the tax withholding under Secs. 1445(a) and (c) applies to all foreign persons disposing of USRPIs.40

Under Sec. 1445(c)(1)(A), the amount of tax required to be withheld cannot exceed the transferor’s maximum tax liability for the transfer of a USRPI, as determined by the IRS. A determination of the transferor’s maximum tax liability is initiated upon request by either the transferor or the transferee.41 The procedures require the filing of Form 8288–B, Application for Withholding Certificate for Dispositions by Foreign Persons of U.S. Real Property Interests, to apply for a withholding certificate to request reduced tax withholding on the disposition based upon the transferor’s maximum tax liability. The transferor’s maximum tax liability is the sum of the maximum amount of U.S. income tax that could be imposed on the disposition of a USRPI, plus the amount that the IRS determines to be the transferor’s unsatisfied tax withholding liability.42

Transferees may request a maximum tax liability determination either before or after the transfer of a USRPI. However, those transferee determination requests can only be made to cure overwithholding errors. Transferees, nevertheless, have primary tax withholding responsibility before a transaction occurs. Factors such as time constraints and needing financial information from the transferor to establish the maximum tax liability make any possibility of reduction in withholding tax difficult to achieve before the disposition occurs.43 IRS officials are required to respond to a request for a determination of tax liability within 90 days after receiving the request.44

An exception applies to the disposition of a personal residence when the gross amount realized is less than $300,000.45 For a USRPI disposition that is not a disposition under Sec. 1445(a), but instead is one under Sec. 1445(e)(1)(A), the tax withholding rules are different. A U.S. partnership, the trustee of a U.S. trust, or the executor of a U.S. estate is generally required to deduct and withhold tax equal to 35% of the gain realized on the disposition of a USRPI,46 to the extent that it is allocable to a partner or beneficiary who is a “foreign person.”47 (Sec. 1445(a), by contrast, requires tax withholding of 15% on the gross amount realized.) The distributive share allocable to each partner of the gain realized on the disposition of a USRPI is determined under Sec. 704 principles and rules.48 Tax withholding on the gain is feasible because the partnership, trustee, or executor is the withholding agent that computes the gain on the disposition.

Real property interest gains are subject to Sec. 1446 tax withholding (withholding on foreign partner’s ECI), not Sec. 1445 tax withholding (FIRPTA) when the partnership is a domestic partnership, otherwise subject to both tax withholding requirements (Secs. 1445 and 1446) on any gain from a USRPI disposition, provided the partnership fully complies with Sec. 1446 withholding and tax reporting requirements. If tax amounts are withheld under Sec. 1445 by the partnership at the time of the USRPI disposition, the amounts can be “credited against” the Sec. 1446 tax liability.49

Election to treat income from real property as ECI

A foreign nongrantor trust that receives rental income from real property located in the United States may make a tax election under Regs. Sec. 1.871–10 to treat all the income from real property located in the United States as ECI, if the property is held for the production of income.50 The election may be made only for U.S. real estate income that is not in facteffectively connected with the conduct of a trade or business within the United States (because it is held for investment for the production of income).51

In contrast, net rental income received by an NRA (or a nongrantor foreign trust) as a partner in a U.S. partnership with U.S. real property rental income would be classified as ECI (and thus not subject to a Sec. 871(d) tax election). In the absence of the election, no operating expenses are deductible from the gross rents reported (i.e., treated and reported as income not effectively connected with the conduct of a U.S. trade or business under Sec. 871(a)(1)(A)).

U.S.-source fixed or determinable, annual or periodic income (FDAP)

U.S.-source FDAP income includes dividends, rents and royalties, annuities, and certain interest income from bonds and other debt obligations (taxable, unless qualified under the “portfolio interest exemption” (Sec. 871(h)) or a tax treaty provision), gains from certain dispositions of timber, coal, or domestic iron ore held for at least one year, income from certain original issue discount obligations, and gains from the disposition of certain intangible property where payments are contingent on productivity, use, or disposition of the property.52

U.S. income tax will not be imposed on a foreign nongrantor trust’s receipt of interest income from the following sources:

- Interest from a U.S. bank, savings and loan or similar association, or insurance company unless the income is ECI.53

- Portfolio interest, unless ECI, which includes original issue discount interest that is paid on certain obligations of U.S. persons issued after July 18, 1984.54

- Original issue discount on obligations that mature in 183 days or less from the date of issue, unless ECI.55

- Certain interest-related dividends and short-term capital gain dividends from a regulated investment company (mutual fund).56

Tax deductions allowable for U.S. tax purposes

When determining how much of its taxable income is ECI for U.S. tax purposes, a foreign nongrantor trust reduces its effectively connected gross income (or gross income treated as effectively connected) by the deductions that are “connected” with the income.57 Regs. Sec. 1.873–1 determines the apportionment and allocation of deductions for this purpose. Regs. Sec. 1.873–1(a)(1) stipulates that “the proper apportionment and allocation of the deductions with respect to sources of income within and without the United States shall be determined as provided in part I (section 861 and following), subchapter N, chapter 1 of the Code.” Further, “[t]he ratable part (portions of allowable deductions) shall be based upon the ratio of gross income from sources within the United States to the total gross income. See [Regs. Secs.] 1.861–8 and 1.863–1.”

Regs. Sec. 1.861–8(a)(1) provides that “the operative sections [as applied in this section in determining taxable income of the taxpayer] include . . . section[ ] 871(b) [i.e., ECI] . . . (relating to taxable income of a nonresident alien individual . . . which is effectively connected with the conduct of a trade or business in the United States).” Accordingly, a foreign nongrantor trust is allowed to use those procedures to determine its taxable income for the tax year with regard to ECI.

Expenses properly allocated to ECI

The tax treatment and tax reporting of a foreign nongrantor trust’s administrative expenses paid, such as professional fees (accounting, tax, and legal fees), which are directly attributable to calculating and reporting the trust’s ECI for the tax year, are not clear. Regs. Sec. 1.861–8 does provide guidance on the tax treatment and reporting of the allocation and apportionment of expenses for determining taxable income from sources within and outside the United States by providing rules for that allocation.

A taxpayer to which this section applies is required to allocate deductions to a class of gross income and then apportion deductions within the class of gross income between the statutory grouping of gross income (or among the statutory groupings) and the residual grouping of items of gross income.58 Classes of gross income enumerated in Sec. 61 include “distributive share of partnership gross income” (ECI).59 Legal and accounting fees and expenses are ordinary and necessary, are definitely related and allocable to specific classes of gross income or to all of the taxpayer’s gross income, and are allocated as provided in Regs. Sec. 1.861–8(e)(5).

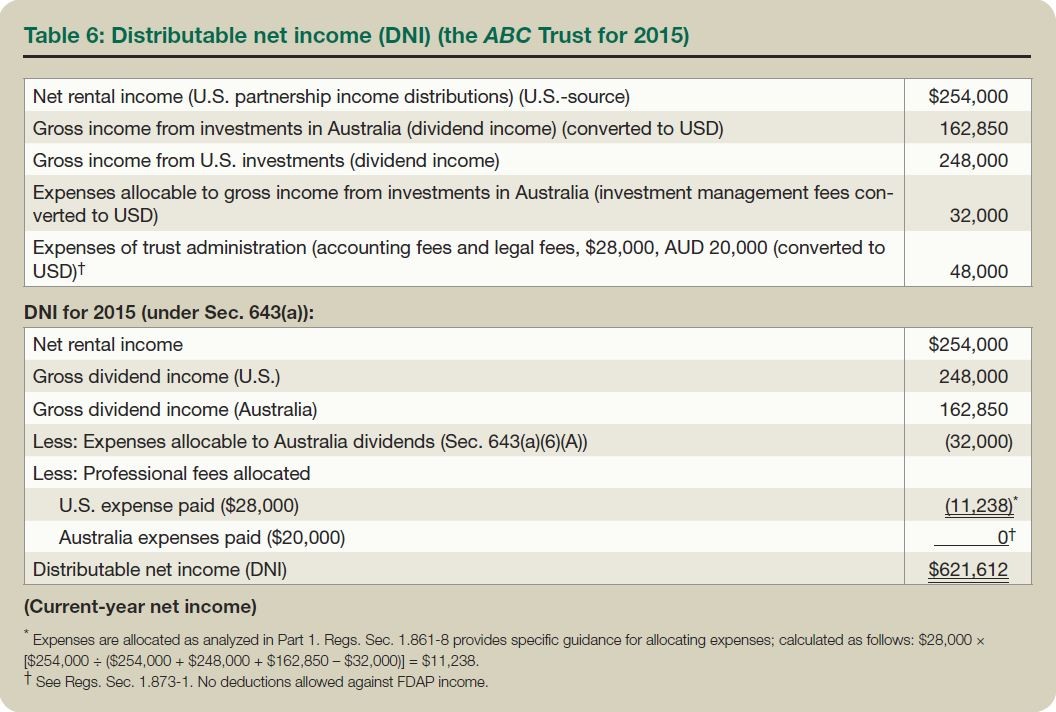

Therefore, the calculated deductible amount of professional fees paid by the foreign nongrantor trust is determined by allocation and apportionment procedures, allocated to the ECI for the tax year, following the guidance in Regs. Sec. 1.861–8, as discussed above. This amount is shown as a reduction of gross income for distributable net income (DNI) purposes. Unfortunately, reporting this amount on Form 1040NR, U.S. Nonresident Alien Income Tax Return, because of its inadequate reporting format for foreign estates and trusts, is difficult for all parties to comprehend (thus, the resulting tax preparation and IRS processing is complex and subject to confusion). However, the tax reporting and treatment of this deduction for U.S. tax purposes will be illustrated in Part 3 of this article.

Other deductions

The following tax deductions are allowable to the foreign nongrantor trust for U.S. tax purposes in determining its taxable income, regardless of whether it has ECI:

- The deduction for casualty or theft losses allowed by Sec. 165(c)(2) or (3), but only if the loss was from property located in the United States;

- The deduction for charitable contributions allowed by Sec. 170; and

- The exemption allowed under Sec. 642(b).60

These deductions, as indicated above, are reported on Form 1040NR for the tax year. No deductions are allowable or allocable against U.S.-source FDAP income, except to the extent the income is properly classified as ECI.

Application of a foreign tax credit

In some cases, a foreign nongrantor trust may pay a foreign income tax in the country of its residence in the tax year that it reported U.S. ECI on its U.S. fiduciary income tax return. For U.S. tax purposes, that foreign income, war profits, or excess profits tax paid on that income may, subject to certain limitations, be permitted as a tax credit (or tax deduction under Sec. 164(a)(3)) against the trust’s U.S. income tax liability.61 The total amount of the foreign tax credit, if applicable, is limited:

- To the proportion of U.S. tax against which the tax credit is taken as to the trust’s taxable income from foreign sources bears to its entire taxable income with regard to ECI;62

- The tax credit is not allowed against any income tax imposed on income not effectively connected with a U.S. trade or business;63 or

- To the extent that the tax credit is properly allocable to the trust’s beneficiaries.64

U.S. tax rates imposed on income

ECI received and reported by the foreign nongrantor trust for the tax year is subject to the same U.S. tax rates that apply to domestic trusts under Sec. 1(e) or 55.65 Sec. 1(h) imposes tax rates between 15% and 28% on long–term capital gains, but only certain capital gains are taxable to the foreign nongrantor trust as previously discussed.

Withholding on U.S.-source income

Importance of the tax withholding certificate

A primary duty of the foreign fiduciary is to obtain signed withholding certificates from the beneficiaries and prepare one for the entity before U.S.-source income is collected or reported by the withholding agents. Form W–8BEN–E, Certificate of Status of Beneficial Owner for United States Tax Withholding and Reporting (Entities), is used by foreign entities to document their tax status for purposes of Chapter 3 (withholding on payments to foreign persons) and Chapter 4 (FATCA) for FDAP payments, as well as for certain other Code provisions.

The form has 30 parts; however, Part I, “Identification of Beneficial Owner,” contains detailed tax information to profile the entity’s type, address, and individual taxpayer identification number (ITIN) or taxpayer identification number (TIN). Part XXVI, “Passive NFFE,” applies to most foreign trusts and estates. Part XXX, “Certification,” contains declarations that the preparer (or authorized agent) attests to by his or her signature. The form is provided to each withholding agent, not filed with the IRS, and is generally valid starting with the date signed and ending on the last day of the third succeeding calendar year after the year the form was signed (unless a change of circumstances makes the form incorrect).66

The withholding agent or payer of income may rely on a properly completed Form W–8BEN–E to treat a payment as being associated to a foreign entity that beneficially owns the income amounts paid. In addition, by completing Part III, “Claim of Tax Treaty Benefits,” the agent can apply a reduced tax treaty rate, or exemption, to the tax withholding amount on the income payment. Failure to provide the form to the agent may require the agent to withhold tax at a 30% nonrefundable rate for each income payment.67

If the foreign nongrantor trust or foreign estate is receiving income that is ECI allocated to the entity through a partnership, the fiduciary will provide Form W–8ECI, Certificate of Foreign Person’s Claim That Income Is Effectively Connected With the Conduct of a Trade or Business in the United States, to an authorized representative of the partnership for Sec. 1446 withholding. The beneficial owner of income paid to a foreign partner that is a foreign complex trust or a foreign estate is the trust entity or estate itself.68

Form W–8BEN, Certificate of Foreign Status of Beneficial Owner for United States Tax Withholding and Reporting (Individuals), is to be signed and completed by the foreign beneficiaries of the nongrantor trust or foreign estate to document their requirements for Chapter 3 and 4 purposes. The form is valid for the same time period as Form W–8BEN–E, as indicated previously. Form W–9, Request for Taxpayer Identification Number and Certification, is provided to the U.S. beneficiary to sign and certify his or her filing status as a U.S. person. Additional information is provided in the author’s previous article.69

The foreign beneficiaries can obtain ITINs by filing Form W–7, Application for IRS Individual Taxpayer Identification Number. The applicant mails the form and supporting identification documentation (Form W–7 applicant package) to the IRS at an IRS Taxpayer Assistance Center or submits the package to a community–based certified acceptance agent or in person to the IRS at certain IRS Taxpayer Assistance Centers.70 Under the new provisions of Sec. 6109, as enacted by the PATH Act of 2015,71 ITINs issued after 2012 expire on Dec. 31 of the third consecutive tax year of nonuse. Those issued before 2012 expire on a rolling schedule based upon the date of issuance unless the ITIN has already expired due to nonuse for three consecutive years.

Application of U.S. tax withholding

In general, foreign nongrantor trusts are subject to U.S. tax withholding on certain items of income that are received from U.S. sources that are not ECI. That income, FDAP, as previously described, is subject to a flat 30% tax withholding (or lower tax treaty provision rate), which is the responsibility of the withholding agent to collect and remit to the U.S. Treasury. The withholding agent is generally the last person (or financial institution) who handles the U.S.-source income item before the payment, net of withholding tax, is remitted to the foreign taxpayer or the entity’s foreign agent. Under these procedures, Chapter 3 of Subtitle A of the Code, “Withholding of Tax on Nonresident Aliens and Foreign Corporations,” applies.72 The withholding agent would provide Form 1042–S, Foreign Person’s U.S. Source Income Subject to Withholding, to the fiduciary to report the category of each income item and the tax withholding amount.

If income (including FDAP income) is ECI, tax withholding is generally not required. A foreign entity can qualify for this exemption if it has a U.S. permanent establishment or place of business. However, U.S. partnerships that have taxable income that is ECI (or that is treated as ECI), do have a withholding obligation if the income is allocable to a foreign partner (i.e., the foreign nongrantor trust) under Sec. 704.73 The tax rate on that withholding is the highest rate of tax specified in Sec. 1(e) for the foreign nongrantor trust or foreign estate.

A foreign partner may claim a Sec. 33 withholding tax credit for its share of any Sec. 1446 tax paid (as withheld on the foreign partner’s income allocation) by the partnership as computed and reported on the partner’s U.S. income tax return.74 The tax return would report the income items making up its allocable share of the partnership’s effectively connected taxable income (ECTI) for the tax year. A foreign partner may substantiate proof of payment (the amount of its tax paid under Sec. 1446) to be applied to its U.S. tax liability by attaching a copy of Form 8805, Foreign Partner’s Information Statement of Section 1446 Withholding Tax, with the Form 1040NR that the partnership provides to the partner for the tax year.

The foreign trust or foreign estate must provide a copy of the Form 8805, as provided by the partnership, to each of its beneficiaries. Each beneficiary may claim the tax credit by attaching the Form 8805 to the beneficiary’s U.S. income tax return. In addition the foreign estate or trust must provide a statement informing each beneficiary of the allocated amount of Sec. 33 credit for withholding tax that the fiduciary elects to allocate to the beneficiary on his allocable share of the income distribution.

No official IRS form is available for making this statement regarding Regs. Sec. 1.1446–3(d) tax reporting. Until an official IRS form is available, the statement must contain the following information:75 (1) the name, address, and TIN or ITIN of the entity; (2) the name, address, and TIN of the partnership; (3) the amount of the partnership’s ECTI allocated to the entity for the partnership’s tax year, as shown on Form 8805; (4) the amount of Sec. 1446 tax the partnership paid on behalf of the entity; (5) the name, address, and TIN or ITIN of the beneficiary of the entity; (6) the amount of the partnership’s ECTI allocated to the entity for purposes of Sec. 1446 tax that is allocated to and included in the beneficiary’s gross income; and (7) the amount of Sec. 1446 tax paid by the partnership on behalf of the entity that the beneficiary is entitled to claim on the U.S. income tax return as a Sec. 33 credit.

The statement furnished to each beneficiary must be attached to the foreign trust’s or foreign estate’s U.S. income tax return for the tax year.76 Each beneficiary of the entity must attach the statement provided by the fiduciary, as well as a copy of the Form 8805, to the beneficiary’s U.S. income tax return for the tax year in which it claims a credit for the Sec. 1446 tax.77 Where the entity has multiple beneficiaries, each beneficiary may claim a portion of the Sec. 1446 tax that may be claimed by all beneficiaries as a tax credit in the same proportion as the amount of ECTI that is included in each beneficiary’s gross income bears to the total amount of ECTI included by all beneficiaries for the tax year.78

Further information about specific guidance regarding tax withholding on foreign taxpayers in the case of trusts and estates is explained on pages 802 through 805 of the article “Reporting Trust and Estate Distributions to Foreign Beneficiaries: Part 1,” in the December 2012 issue of The Tax Adviser. Regs. Sec. 1.1441–5 provides specific guidance on tax withholding for trusts and estates with foreign beneficiaries. Similar procedures apply to foreign beneficiaries of foreign nongrantor trusts or foreign estates who receive distributions of U.S.-source income from the entities. In general, tax withholding is required unless the payer has received appropriate documentation indicating that withholding is not required (or a lower withholding rate applies) and that person has no reason to believe that the documentation is inaccurate.79

U.S. withholding taxes credited to the U.S. beneficiaries

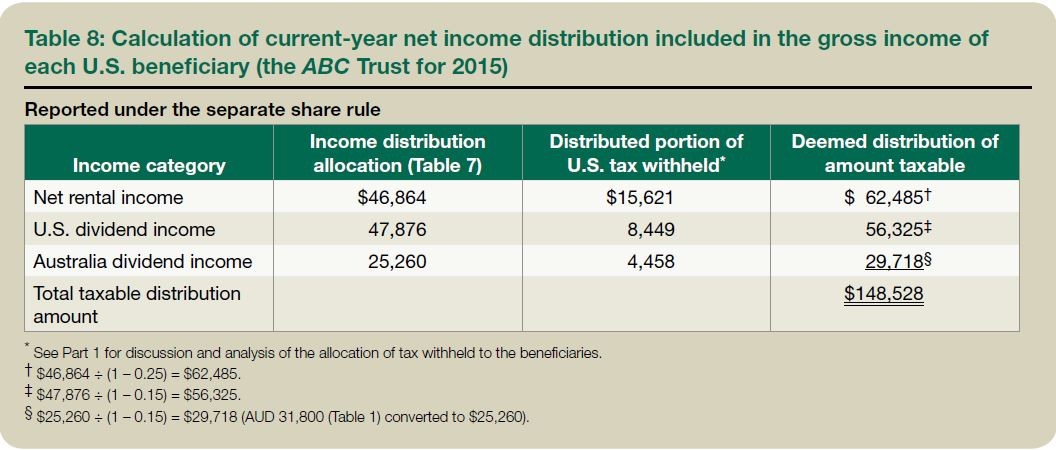

If the foreign nongrantor trust had FDAP income, income from the disposition of a U.S. real property interest, or income distributions from a domestic partnership (ECI), the entity likely paid withholding taxes under Sec. 1441, 1445, or 1446. IRS regulations provide that a U.S. beneficiary who receives an income distribution from a foreign trust that includes U.S.-source income from which U.S. tax has been withheld must include in his or her distributive income share the amount of the allocated tax withheld on those income items.80 As a result, the beneficiary’s distribution is “grossed up” for the allocable amount of withholding tax, which he or she can claim as a credit against his or her personal income tax liability. Where the investment is held in the name of a fiduciary for an estate or trust, and that fiduciary is an NRA, under Regs. Sec. 1.1441–3(f), tax withholding is required on the U.S.-source income even if the income beneficiaries are citizens or residents of the United States.81

If income from sources within the United States has been transferred abroad, it is still treated as being from U.S. sources.82 So, for example, if U.S.-source income is paid to the foreign trust’s trustee who then distributes that income to the U.S. beneficiaries, it is still treated as U.S.-source income.83 If satisfaction of a tax liability of the beneficial owner by a withholding agent constitutes income to the beneficial owner and that income is of a type subject to tax withholding, the amount of the tax payment deemed made by the withholding agent for purposes of Regs. Sec. 1.1441–3(f) is determined under the “gross–up formula” in Regs. Sec. 1.1441–3(f)(1). The payment constitutes additional income to the beneficial owner based upon all the facts and circumstances, including any agreements between the parties and applicable law. The formula as described in the regulation is as follows: Payment [taxable] = Gross payment without withholding ÷ [1 – (tax rate)].

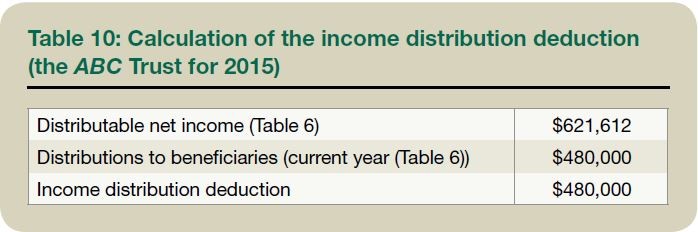

As a result, the fiduciary will charge the tax payment allocated to the U.S. beneficiary’s income distribution to income as a payment on behalf of that beneficiary. The U.S. beneficiary will be subject to U.S. tax on the grossed–up taxable payment and receive a corresponding tax credit for the tax withholding on his or her individual income tax return for that tax year. The entity reports (as an income distribution deduction) that amount without a deduction for the amount of withholding tax required to be withheld as reported on the “foreign nongrantor trust beneficiary statement,” as prepared and submitted by the trustee. The amount of the beneficiary’s share of allocated tax actually withheld is allowed as a tax credit against the total income tax for the year as computed in the U.S. beneficiary’s tax return.84

The gross–up rule described above also applies to Chapter 3 tax withholding on ECI, if a U.S. beneficiary is subject to taxes imposed on his or her allocable share of ECI paid to the foreign trust. The portion of tax withheld at the source that is allocable to the income share distributed to the U.S. beneficiary will be similarly allowed as a tax credit against the total income tax for the year as reported in the beneficiary’s tax return, and any excess can be refunded.85 Again, those amounts are required to be reported by the trustee on the beneficiary’s foreign nongrantor trust beneficiary statement to enable him or her to report the amounts correctly.

If the amount of the income item is subject to withholding tax that is paid in a currency other than the U.S. dollar, the amount of Sec. 1441 withholding tax is determined by applying the applicable rate of withholding in the foreign currency amount and converting the amount withheld into U.S. dollars on the date of payment at the spot rate (as defined in Regs. Sec. 1.988–1(d)(1)) in effect on that date. A withholding agent making payments in foreign currency may use a month–end spot rate or a monthly average spot rate. The agent may also use the spot rate on the date the taxes are deposited (as determined by Regs. Sec. 1.6302–2(a)), provided that the deposit is made within seven days from the date of the income item payment subject to the withholding obligation. These procedures must be followed consistently from year to year.86

Reporting U.S. beneficiary distributions from foreign nongrantor trusts

As previously discussed in this article, the trustee of the foreign nongrantor trust may be required to file Form 1040NR to report the U.S.-source income and tax withholding for the tax year. Form 1041–T, Allocation of Estimated Tax Payments to Beneficiaries, is filed with the IRS by many U.S. domestic trusts and estates to report the allocation of estimated income tax payments paid by the trust or estate to its beneficiaries (by a timely tax election under Sec. 643(g)). Many practitioners also file Form 1041–T separately with the IRS, following the IRS instructions and due date, as well as attach a copy with Form 1040NR, to report the U.S. income tax withholding allocated to U.S. beneficiaries, as previously discussed above. Those procedures are intended to alleviate possible “matching errors” with IRS records to avoid correspondence to rectify those reporting issues.

Unfortunately, the IRS has not provided specific guidance on the U.S. tax form to use as a mechanism to track the U.S. beneficiary’s Social Security number on Form 1040NR or Form 1041–T for the trust’s allocated share of tax withholding distributable to each beneficiary. As analyzed above, Regs. Sec. 1.1441–3(f) provides guidance that the allocation and matching to each applicable beneficiary should be properly reported. In addition, Sec. 1462 clearly stipulates that the tax withheld at source should be included as income on the return of the income recipient. It further stipulates that any tax so withheld is credited against the amount of income tax as computed on the recipient’s individual income tax return.

By filing Form 1041–T to report the allocations of tax withheld to each applicable beneficiary, U.S. and foreign ones, practitioners will make a reasonable attempt to avoid matching problems with the tax payments that withholding agents collect and deposit with the IRS as reported under the foreign trust’s employer identification number (EIN) or ITIN (on Forms 1042-S and 8804). This author recommends that a separate Form 1041–T be filed with the entity’s Form 1040NR (designating “Section 1441(b) Taxes” on the top of one, and “Section 1446(b) Taxes” on the top of the other). As discussed above, the U.S. beneficiary’s “foreign nongrantor trust beneficiary statement” will be attached to the Form 1040NR filed by the trustee. Submitting Form 1041–T directly to the IRS, within 65 days after the tax year–end date, and attaching it to the filed Form 1040NR, will more likely avoid matching discrepancies in IRS processing procedures. Until the IRS provides specific guidance on this tax reporting (i.e., a tax form with procedures to properly report the tax year’s allocation of tax withheld to U.S. and foreign beneficiaries by the trustee), filing Form 1041–T appears to be an effective method to safeguard these payment allocations under Sec. 1462 and Regs. Sec. 1.1441–3(f).

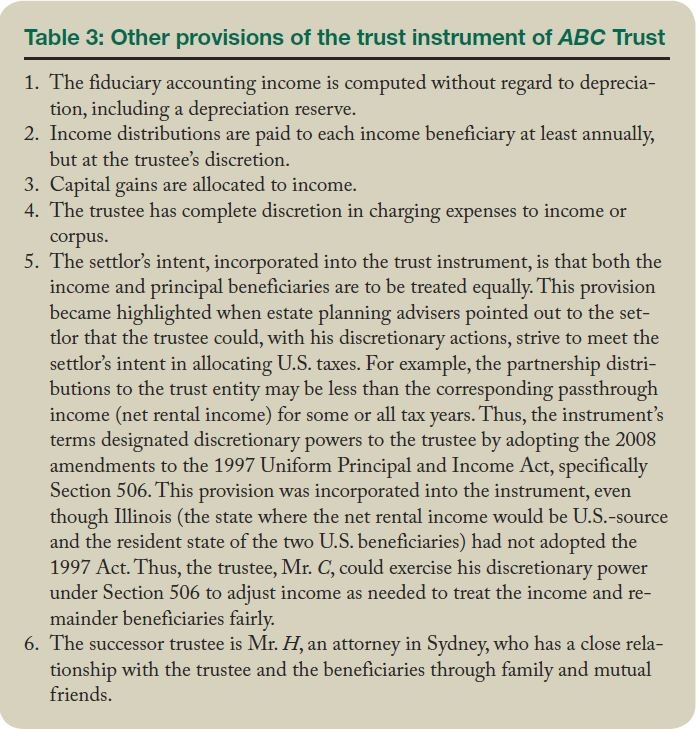

Foreign Nongrantor Trust Beneficiary Statement – FNGT Beneficiary Statement

- The trust’s basic identifying information and the first and last day of the tax year to which the statement applies,

- A description and fair market value of property distributed,

- A statement regarding whether the trust appointed a U.S. agent. − If the trust did not appoint a U.S. agent, there must be a statement that the trust will permit either the IRS or the U.S. beneficiary to inspect and copy the trust’s books and records to determine the U.S. tax treatment of any distribution or deemed distribution.

- An explanation or sufficient information regarding the appropriate U.S. tax treatment of any distribution or deemed distribution, and

- A statement identifying whether any grantor of the trust is a partnership or a foreign corporation. If the beneficiary used or was required to use the default calculation for trust distributions, Form 3520, Part III, Schedule A:

- Ensure the beneficiary’s income tax return reported the amount on Schedule A, line 36 of the Form 3520 as income, as an example, on Form 1040 the income would be reported on Schedule E, Part III, Income or Loss from Estates and Trusts,

Currently, no official IRS form exists for a foreign nongrantor trust beneficiary statement; however, Notice 97–34 and the IRS Instructions to Form 3520, Annual Return to Report Transactions With Foreign Trusts and Receipt of Certain Foreign Gifts, provide clarification of the information needed for the trustee to correctly report the tax information for the U.S. beneficiary for the tax year. The information should be reported by the fiduciary so that each U.S. beneficiary can determine the appropriate tax treatment of any applicable trust distribution(s) for the tax year. According to Notice 97–34, information similar to the tax information required to prepare Schedule K–1 (Form 1041), Beneficiary’s Share of Income, Deductions, Credits, etc., is adequate. The statement need not be filed as an attachment to Form 1040NR; however, attaching the statement might be prudent if questions are raised regarding the trust’s transactions because the statement pertains to each beneficiary for the tax year. Perhaps a more important reason for the trustee to prepare the statement in a diligent manner is to enable the beneficiary to accurately report the information on Form 3520, which requires that information on Part III. If the beneficiary lacks that information because the trustee did not prepare a statement, the beneficiary could be in the position of inadvertently electing the default method, resulting in being subject to the harsh tax consequences of the throwback rules, which are discussed below. These procedures are explained in Notice 97–34 and Form 3520 instructions.

Under the throwback rules, any distribution from a foreign nongrantor trust, whether from principal or from income, will be treated for U.S. tax purposes as an accumulation distribution, which is includible in the beneficiary’s gross income (subject to ordinary income tax rates and an interest charge), unless the IRS was provided adequate records to determine the proper tax treatment of those distribution(s).87 By designating the current tax year distribution(s) as a “Current Year Income Distribution(s), on the Beneficiary’s Statement,” the beneficiary will be in a position to file an accurate income tax return for the tax year (assuming that the information on the statement is accurate and can be sufficiently substantiated).

Caution: Although certain types of U.S.-source and foreign–source income items are not taxable to the foreign nongrantor trust, as discussed earlier in this article, those items are taxable to the U.S. beneficiary and, therefore, should be disclosed on the foreign nongrantor trust beneficiary statement. Some examples include U.S. bank deposit interest income, capital gains from security sales (not effectively connected with a U.S. trade or business), foreign dividends, foreign interest, and foreign rental income.

Form 3520 filed by the U.S. beneficiary

Form 3520 is required to be filed for any tax year by a U.S. person who received (directly or indirectly) a distribution from a foreign trust.88 Each distribution for the tax year is reported in Part III of the Form 3520, which is filed by the due date of the beneficiary’s U.S. income tax return or the extended due date, Oct. 15, if a timely extension is filed. On the form, the U.S. person is required to report the gross reportable amount, which includes the gross amount of the distributions from a foreign trust.89 Failure by the beneficiary to properly report a distribution(s) on his or her Form 3520 and/or individual income tax return for the applicable tax year could subject the the beneficiary to a tax penalty equal to the greater of $10,000 or 35% of the gross reportable amount.90

The U.S. beneficiary can, in some cases, satisfy reasonable–cause requirements to avoid or reduce any penalties, in the event that a distribution is not correctly reported in a timely manner. However, the fact that a foreign jurisdiction would impose a civil (or criminal) penalty on the taxpayer (or any other person) for disclosing the required information is not acceptable as reasonable cause.91 In addition, the trustee’s refusal to provide information for any other reason, including difficulty in producing the required information or any provisions in the trust instrument that prevent the disclosure of required information, will not be considered reasonable cause.92 It is the beneficiary’s responsibility, rather than that of the entity’s fiduciary or U.S. agent, to report the correct tax information on Form 3520.93

The HIRE Act of 201094 provides that a taxable distribution occurs in a tax year that a trustee of a foreign trust permits the “uncompensated personal use” of any trust property directly or indirectly by a U.S. beneficiary or any related U.S. person. If such an event occurs, the FMV of the use of the property is treated as a taxable distribution to the U.S. beneficiary (or related party).95 A later return of the property (to the trustee) without timely payment for the use of the property would be disregarded and treated instead as a taxable distribution for tax purposes.96 This statutory provision does not apply to the extent that the trustee is paid the FMV for the use of the property within a reasonable period of time after the (personal) use.97 Any uncompensated use of trust property treated as a taxable distribution, as discussed above, would be reportable on Form 3520 and the taxpayer’s individual income tax return for the tax year. Neither the statute nor the committee reports provide specific guidance on issues of uncompensated use, such as defining a “reasonable period of time” after use for consideration to be paid or guidelines on measuring the FMV of the use. The IRS has yet to formulate regulations or guidance on these issues. Therefore, caution is advised to seek professional assistance in tax reporting when this issue arises. Other “Practice Tips” are specified in the author’s previous article.98

Form 8938 filed by the U.S. beneficiary

U.S. beneficiaries may be required to file Form 8938, Statement of Specified Foreign Financial Assets, with their individual income tax return, for tax years ending after Dec. 19, 2011.99 The tax return filing requirements under the final regulations indicate that the form is required by a U.S. person holding an interest in foreign financial assets exceeding $50,000 at the end of the tax year or $75,000 during the tax year. The regulations further provide that an interest in a foreign trust or foreign estate does not have to be included on a statement of foreign financial assets (SFFA), unless the specified individual (SI) either knows or has reason to know of the existence of the interest based upon readily accessible information.100 Receipt of a distribution from the foreign trust or foreign estate constitutes actual knowledge of its existence for Sec. 6038D purposes. Simplified valuation rules apply that allow an SI to place a value of $0 on the SFFA in years that no distribution is received and the SI does not know the value of the interest based upon readily accessible information.101

If readily accessible information is available to value the beneficiary’s interest, then the maximum value of that interest is the sum of (1) the FMV, determined on the last day of the applicable tax year, of all currency and other property distributed by the foreign trust or estate during the year to the SI as a beneficiary; and (2) the FMV, determined on the last day of the year, of the SI’s right as a beneficiary to receive mandatory distributions from the entity.102 To alleviate the burden of duplicative tax reporting, the IRS instructions provide exceptions for reporting SFFAs on Form 8938. The tax form, in Part IV, “Excepted Specified Foreign Financial Assets,” has a line to indicate the “Number of Forms 3520” filed for the corresponding tax year. The IRS regulations stipulate that the SI is not required to report an SFFA on Form 8938, provided that the SI already reports that SFFA on one of the designated international information returns that was timely filed with the IRS (Form 3520 being one of those designated).103

Failure to comply with Sec. 6038D reporting requirements subjects the taxpayer to civil penalties. Failure to file Form 8938 in a timely manner can result in a penalty of $10,000.104 The penalty can increase if the taxpayer does not rectify the reporting and filing after being contacted by the IRS. The penalty will not apply if the SI can demonstrate that the violation was due to reasonable cause and not due to willful neglect.105 New Sec. 6501(e)(1)(A) created a longer six–year assessment period for certain foreign income omissions on taxpayer income tax returns. The new provision applies to omissions of income from SFFAs that exceed $5,000.

FinCEN Form 114, Report of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts (FBAR), must be filed if the U.S. beneficiary or U.S. trustee of a foreign nongrantor trust has a financial interest in or signature authority or other authority over any financial accounts, including bank, securities, or other types of financial accounts in a foreign country, if the value of those accounts exceeds $10,000 for the tax year. FinCEN Form 114 must be filed by April 15 of the calendar year, for years after 2015, but an extension to Oct. 15 is automatic and does not require an extension request. The form must be filed electronically through the BSA E–Filing System.106 For trusts, if a U.S. person beneficiary has a present beneficial interest in more than 50% of the entity’s assets or receives more than 50% of the current year’s income, the beneficiary reports the entity’s foreign financial accounts (subject to the $10,000 reporting threshold).107 However, if the trust, trustee of the trust, or agent of the trust is a United States person, the U.S. beneficiary does not have an FBAR reporting obligation.108

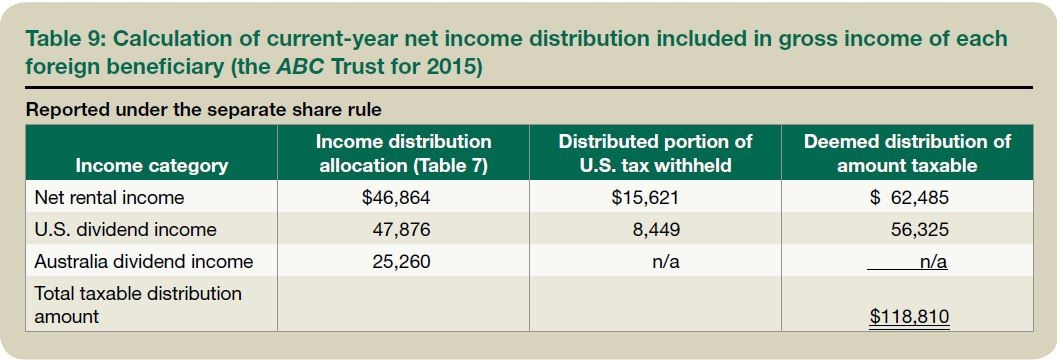

Distributions from a foreign nongrantor trust to foreign beneficiaries

The NRA beneficiary of a foreign nongrantor trust is required to file Form 1040NR only if the full amount of federal U.S. withholding tax is not collected by the payers (withholding agents) for the U.S.-source income allocable to the NRA’s share of the trust’s DNI for the tax year. However, he or she is required to file Form 1040NR if the NRA has an income distribution in the current tax year that represents an allocated share of ECTI as a beneficiary (as a result he or she is treated as being engaged in a U.S. trade or business, as previously discussed because of the trust’s income being classified accordingly under Sec. 875(1)).

Sec. 875(2) expressly provides that an NRA who is a beneficiary of an estate or trust that is engaged in any trade or business within the United States shall be treated as being engaged in that trade or business within the United Sates.109 If a partnership is engaged in a trade or business within the United States, the estate or trust as a partner of that entity, is treated as so engaged.110

The NRA would qualify as a U.S. person and, as a result, the foreign beneficiary would be required to file either Form 1040NR or 1040, under the following circumstances:

- The NRA has a physical presence in the United States for 183 days or more in the current tax year;111

- The NRA elects to be a “dual resident” taxpayer of the United States;112 or

- The NRA is engaged in a U.S. trade or business or is an employee of one.113

As a result, unless one of the above exceptions applies to the NRA beneficiary, the trustee of the foreign trust would have no U.S. reporting responsibility for the NRA’s U.S. tax reporting, unless the IRS questions the foreign trust’s transactions or its trust instrument provisions, which might affect the U.S. tax reporting for the NRA beneficiary.

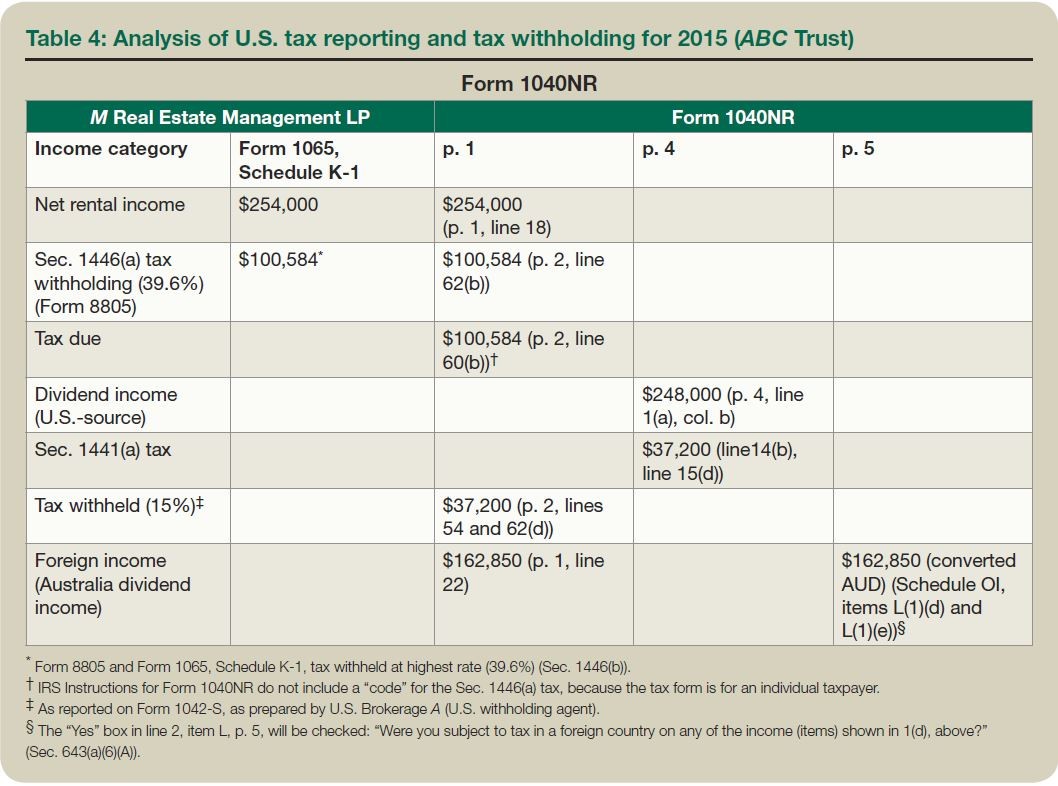

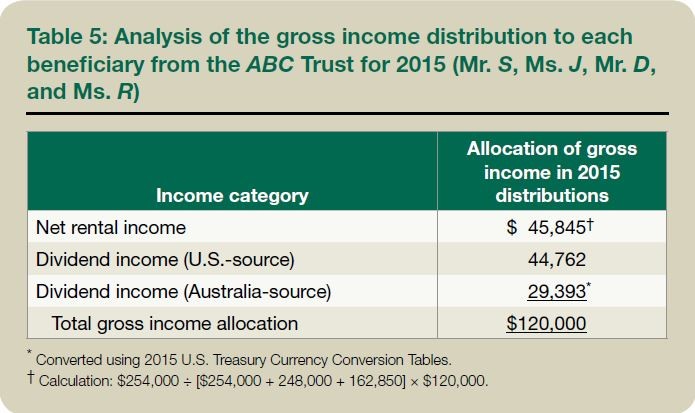

Certain U.S.-source income, specifically ECI, received by the foreign nongrantor trust and distributed to the NRA beneficiary under Sec. 871(b), requires the foreign beneficiary to file Form 1040NR for the tax year to report his or her distributive share of ECTI in the trust’s DNI. As previously discussed in “Application of U.S. Tax Withholding,” on p. 719, a U.S. partnership with a foreign partner (i.e., foreign nongrantor trust) must withhold U.S. tax (under Sec. 1446(b)(2)(A)) and report the tax withheld on Form 8804, Annual Return for Partnership Withholding Tax (Section 1446), to the IRS, and on Form 8805, to the foreign partner. This tax withholding is required at the highest ordinary tax rate for the foreign partner (i.e., Sec. 1(e), or 39.6% for 2015 and 2016 for a foreign nongrantor trust). Part 3 of this article will discuss and illustrate the tax reporting of this income item in a comprehensive example for both the U.S. and NRA beneficiary, as well as the trust.

For the reasons stated above, with regard to the distributive share of ECI income (partnership distributed income), the NRA beneficiary should request, and the trustee should respect the request, that he or she be provided with a foreign nongrantor trust beneficiary statement with the same tax information and format as described above for the U.S. beneficiary. The NRA beneficiary could then file a complete and accurate Form 1040NR with the tax information the foreign trust previously reported to the IRS for the tax year.

Consistency requirement for trust beneficiaries

Beneficiaries of a trust or estate must treat any reported item on their own individual income tax return consistent with the tax treatment of that item on the fiduciary income tax return.114 For this purpose, a “reported item” is any item for which the trust or estate must furnish information to the beneficiary. Exceptions to this rule apply when:

- The beneficiary’s tax treatment on a return of any reported item is (or may be) inconsistent with the reported treatment of the item on the fiduciary’s return or the trust did not file a return; and115

- The beneficiary files a statement identifying the inconsistency with the IRS.116

Form 8082, Notice of Inconsistent Treatment or Administrative Adjustment Request (AAR), is the tax form that the beneficiary completes to attach to his or her income tax return to explain the inconsistency. A beneficiary is treated as having complied with these requirements for the reported item, if:

- The taxpayer demonstrates to the satisfaction of IRS personnel that the tax treatment of the item on his or her income tax return is consistent with the correct treatment of the item on the schedule furnished by the fiduciary (the taxpayer would need to substantiate authoritative tax law references that support this different treatment); and

- The taxpayer elects to have this rule apply.117

Obviously, in the case of a U.S. beneficiary of a foreign nongrantor trust, the beneficiary should use caution under those circumstances. Sound professional guidance would certainly be beneficial, considering the potential penalties.

Fiduciary income tax return reporting and tax year

Even though a foreign nongrantor trust may file a tax return in its resident tax jurisdiction on a fiscal–year basis, calendar tax year reporting is required for Form 1040NR.118 Therefore, the foreign trust would be required to adopt a calendar tax year for U.S. filing purposes under Sec. 645(a). In addition, Sec. 6654(1) provides that any trust that is subject to federal income tax is required to pay estimated income tax payments.

Form 1040NR is required to be filed by a nongrantor trust or foreign estate, as indicated in the Form 1040NR instructions, following the provisions of Subchapter J of the Code. Treasury regulations require a return to be filed in situations including where:

- The trust or estate was engaged in a trade or business in the United States during the tax year, even if no income was derived from those activities; or

- The trust or estate had received FDAP income in the tax year that is subject to U.S. taxes, unless the tax liability is fully satisfied by tax withholding;119 or

- The trust was qualified as a U.S. trust for part of the tax year and as a foreign trust at the end of the same tax year (requiring a “Dual-Status Return” designation at the top of the fiduciary tax return (Form 1040NR) filed for the tax year). The trust should attach a statement (Form 1041, U.S. Income Tax Return for Estates and Trusts) as a schedule showing income for the portion of the year that it was a U.S. trust.120

Under Regs. Sec. 1.6109–1(b), the trustee of the foreign nongrantor trust is required to obtain a U.S. TIN for fiduciary tax return filing and tax withholding purposes. The due date of Form 1040NR is the 15th day of the sixth month following the close of the calendar tax year, unless the trust has a U.S. office or place of business (in that case, it is the fourth month after the tax year end).121

The fiduciary of a foreign nongrantor trust is well–advised to appoint a U.S. agent to act as the foreign trust’s limited agent to respond to any request by IRS officials to examine records or produce testimony or to respond to a summons for records or testimony. The format of the agreement to authorize the U.S. agent under Sec. 6048(b) is outlined in Notice 97–34, Section IV.B., “Appointment of U.S. Agent.” The agent can also be beneficial in handling tax matters with the foreign trust’s or foreign beneficiary’s home country’s tax authorities.

—————————————————————————————————————-

In recent years, international regulatory and tax–compliance global initiatives have raised awareness of and attention to the tax obligations affecting mobile owners of wealth and international financial institutions that operate in multiple jurisdictions. Traditionally, the fiduciary’s duties and responsibility have been to protect the beneficiary’s interest, being charged with legal responsibilities involving prudent care, astute guardianship, and stewardship. Today’s fiduciary is also expected to have and to exercise the ability to process volumes of complex information, while balancing different sources of professional tax and financial advice. Simultaneously, a successful fiduciary respects the dynamics within multiple generations of family members, while considering the nuances that are often deeply embedded within each member’s culture.

Straightforward wills are becoming commoditized so that they are now widely available at low cost, while estate planning is becoming increasingly complex, with a significantly more sophisticated entity structure that requires greater collaboration among professional advisers.1 The issues confronting today’s fiduciaries are not only ones of tax, residence, and domicile. The major legal systems dominate global fiduciary administrations: common law, civil law, and religious law.

People in the Persian Gulf states generally follow Islamic law or Sharia, a religious law that is not tied to a physical location, except in Saudi Arabia, where it is the law of the land.2 Families from the Gulf states tend to be close–knit and give the well–being of the family group priority.3 In contrast, the culture in countries using the common law legal system, including the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, and Australia, tends to be more focused on the individual. Common law legal systems depend on judicial decisions to interpret and, in many cases, create law. Civil law countries, which follow statutory or codified systems, make up most of the other countries in the world. Countries with civil codes tend to have cultures that follow the laws like a rulebook rather than a guide.4

Inheritance laws in civil law jurisdictions are very different from those in common law jurisdictions. For example, common law principles allow older generations to disinherit younger generations or give them unequal shares of property in their trust instrument and/or will. In contrast, civil law countries follow forced–heirship principles, which guarantee that younger generations will inherit a certain share of a parent’s assets. As a consequence, today’s mobile society, which sometimes includes marriages that mix different cultures, complicates traditional estate and trust administration.

Advising clients in ‘private international law’

Difficulties can develop when a trust is administered in a different jurisdiction from where it was created or established. The trust is a legal entity, which can only succeed administratively in a judicial environment where the jurisdiction recognizes the trust under common law principles. In countries where those legal principles are not recognized, the court will not find a rule for conflict of laws according to which it can determine the laws that apply to the trust. For example, even if a judge concludes that a common law country’s law applies, it may be difficult to determine how to translate into the non–common law country’s own law(s) the legal effects that will result from the trust’s facts.5 With these problems confronting fiduciaries and beneficiaries, the Hague Conference on Private International Law (HCCH) developed an international convention on the laws that apply to trusts and whether they are recognized, in 1982. The Hague trust convention (“Convention on the Law Applicable to Trusts and on Their Recognition”) was adopted on July 1, 1985.

Application of the Hague conventions

The HCCH is a global intergovernmental organization that has as its mission the progressive unification of the rules that various countries have adopted to resolve differences among their legal systems.6 Its objectives involve developing international approaches to court jurisdiction, jurisdictional law, and the recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments in a range of areas from banking laws to matters of marriage and personal status.7 The HCCH has 83 member states from around the world, and is attracting nonmember countries that are becoming parties to the Hague conventions.8

Benefits of the Hague conventions

The Hague conventions and their articles create greater legal certainty in difficult cross–border circumstances. For example, under the conventions, a will executed by a testator in accordance with Swedish law will not be deemed invalid in Japan just because it is in a different form.9 To meet its objectives for greater global legal certainty, the HCCH’s Hague conventions must be more widely adopted by additional foreign jurisdictions. Some progress has been made in this ratification process over the last several years.

In terms of specific articles in the convention on trusts, for example, Article 6 stipulates that the legal system that applies to the trust is that which the settlor chose. The settlor’s choice of legal system must be made either expressly or by implication in the terms of the trust instrument.10 If not, Article 7 provides that the trust is governed by the legal system with which it is most closely connected. Under those circumstances, the following facts must be analyzed to ascertain the legal jurisdiction that applies to the trust:

- The location of the trust administration as designated by the settlor;

- The location(s) of the trust’s assets;

- The trustee’s place of residence or business location;

- The objectives or purposes of the trust; and

- The tax jurisdictional laws that apply where each asset is located.11

However, all questions concerning the law of succession must be dealt with according to the law of the state (country of jurisdiction) to which the testator or settlor belonged (his or her domicile) at death.12

Nevertheless, the recognition of a trust’s valid legal establishment according to a foreign jurisdiction’s laws has its limits. According to Article 15 of the convention, a trust’s legal status is not recognized insofar as mandatory provisions of the legal order, as designated by the conflict of rules of the forum, would be violated.13 For example, if assets located in Japan or Germany (civil law jurisdictions) were alleged to have become property of the trust, a Japanese or German judge must apply mandatory provisions of Japanese or German property law to determine that fact of law.14

Guarded optimism in applying the Hague convention

Recently more success stories have occurred in some civil law jurisdictions, and even in other common law jurisdictions, in recognizing the trust and its legal system applications. Two primary reasons point to these successful results:

- The Hague trust convention creates a “common framework” for civil law countries that desire to formally recognize the trust and its legal applications, thus avoiding the question of how the trust will be characterized under local law, an issue that can require complex analysis and legal rulings.15

- The convention provides a “term of reference” for the courts in countries that do not formally recognize trusts, but are presented with the responsibility to determine the application of the local jurisdictional laws, to make judicial decisions about a trust.16

The challenges under the above circumstances will continue to confront professionals and fiduciaries. The quality of the local service providers, the professional team members, and the judiciary, if needed, often determines the final outcome. The jurisdictional rules and enforcing judgments are additional essential criteria for all parties to consider in this process.

Other challenges for trusts in foreign jurisdictions

Trust administration can often involve multiple jurisdictions. A trust, for example, can be created under the laws of Country A, but be administered by a trustee in Country B (and perhaps also Country C). At the same time, the trust can be a tax resident in Country D. These circumstances result in a legal dilemma and raise questions: What law applies to what issues? One question might be whether the trust property in the trust declaration was “alienable” (transferable from the settlor to the trustee’s control at the settlor’s death) “in some form” according to the law of situs.17 Subject to those qualifications, the “conflicts rules” in the Hague convention would determine the law governing the validity of the trust and its terms.18

International wills

Some estate planning attorneys advise the testator to draft a supplemental will to cover only the property owned in a specific foreign jurisdiction (i.e., a foreign codicil to a domestic will). Care is recommended in preparing a codicil because of the risk of revocation of any portion of the original domiciliary will. A supplemental will usually designates the immovable property located in the foreign country, such as real property.19

An alternative is to execute an “international will” to provide for the testator’s foreign ownership of the property. The international will, when drafted to meet the requirements of the International Institute for the Unification of Private Law (UNIDROIT), will be valid in any jurisdiction that has signed the Uniform International Wills Act. Treaty signatories include several foreign countries, as well as the United States, 23 states, and the District of Columbia.20

However, owning foreign property in a civil law country might make such a codicil unnecessary to complete a bequest to a beneficiary, if the property vests in the decedent’s heirs immediately upon the testator’s death. Qualified and experienced legal advice is the best option before proceeding with international estate planning and drafting the necessary legal documents to safeguard foreign assets. Practitioners should exercise caution in coordinating the “situs” will with the nonresident’s primary will to be sure both are valid and enforceable. Mistakes can often result in the accidental revocation of either will.21

Achieving a global understanding of trust situs

One of the objectives of this article is to educate the reader on the nuances of estate and trust administration with a global perspective. The proper income tax reporting of the foreign trust or foreign estate is directly related to these legal issues previously discussed. Determination of the foreign estate’s or trust’s situsis critical. Multiple types of situs can exist simultaneously, including administrative situs, jurisdictional situs, tax situs, and locational situs.

Administrative situs